For Ha kol Olin Shabbat morning

Hello, Shabbat Shalom. I have volunteered to say a few words about our Parasha today. But before I say anything about Pinchas, I need to say a word about a word. The word is: ‘mutable’ and it’s flipside ‘immutable’.

Mutable does not mean what I do on Zoom when the speaker is boring, although sadly I must admit I do mute because I have a short attention span and thanks to modern technology, tedious people are now mutable. Unfortunately for you today, that option is not open to you. So if you have a nap for the next five minutes, I will understand. I will try to keep it interesting though.

This is what mutable means in the academic world – it’s the word for things that can change over time. The opposite of mutable is immutable which means unchanging over time or unable to be changed. I came across this concept a few years ago when I read a fascinating book called What’s Divine about Divine Law by Christine Hayes. In it, she shows that for the ancient Greeks, divine law has to be by definition- rational, true, universal, and immutable. Divine law doesn’t change for the ancient Greeks.

While in the Torah, on the other hand, divine law is divine because it is grounded in revelation with no presumption of rationality, conformity to truth, universality, or immutability. In our tradition, the law can change. And change it often does. There are three powerful examples of that capacity of the law to change in the parasha today. I’ll start with the most obvious one…

Machlah, Noah, Chaglah, Milkah and Tirtzah, the five daughters of Tzelophchad of the tribe of Menashe, want the existing divine law of inheritance to change. They ask Moses that they be granted the portion of the land intended for their father who died without sons. God accepts their claim, changes are made to the divine law and are incorporated into the Torah’s laws of inheritance. That is mutable divine law in action in the Torah itself.

But for me, the more interesting example of the mutability of divine law comes earlier in the parasha, with the very problematic story about a zealot called Pinchas who drives his spear though the belly of Zimri while he is having sex with Cozbi, the Midianite woman. Bravo! Lives are saved and Pinchas is blessed by God. I’m just guessing here that no-one here is comfortable with this story. Luckily, we are not the first Jews who need and want to rewrite the Torah precedent expressed here. The rabbis of the Talmud in Sanhedrin 81 and 82 are extremely critical of Pinchas and his zealous ways. They decide that halachically Pinchas acted on his own and without court sanction. Strangely for the rabbis of the Talmud, they don’t debate it. They say it categorically.

Specifically they say that if Zimri, the victim had turned around and killed Pinchas the Zealot in self-defence, Zimri would be declared innocent in a court of law. Secondly, the Talmud narrows down the permitted zone and rules that if Pinchas had killed Zimri and Cozbi just a moment before or after they had sex, he would have been guilty of murder.

Thirdly, the rabbis of the Talmud say that had Pinchas consulted a Bet Din and asked whether he was permitted to do what he was proposing to do, the answer would have been a clear no. Absolutely not. The permission for zealotry expressed in the torah today is withdrawn in the Gemara.

It clearly states, an individual cannot execute a death sentence without a duly constituted court of law, a trial, evidence and a judicial verdict. Killing without due process is murder. Halachically today, an individual cannot commit murder even to save lives. Don’t even think about it. With techniques like this, the rabbis of the Talmud change the divinely mandated law in many places in the Talmud, and God laughs. Times have moved on and the locus for law is not in the sky anymore but amongst the people.

<

>

The other change we can see in the Parasha today is that we no longer do the festival sacrifices described. Not the sheep or the rams or the cows with their roasted smell that is so pleasing to God. The last change is in leadership. Moses empowers Joshua to succeed him and lead the people into the promised land.

<

>

The parasha is about transitions in law, in leadership and in practice. Change in Jewish life is like a glacier, moving slowly and continually. Occasionally, you catch a glimpse and see the changes for yourself in your own lifetime. When I was growing up, there was a belief that women had to sit upstairs. The only time we ever came downstairs to the men’s section was for our en-masse bat mitzvah ceremony, where batches of girls wearing white were processed twenty at a time.

But change is sometimes maddeningly slow and there are still people today who believe women’s voices cause Erva or licentious or are an embarrassment to the community and as such they may not daven or leyn for the community. Strange I know, but I’m sympathetic because we’ve all experienced for ourselves how closely embedded habit is to justifications of what can’t ever possibly change. But habits become normal, and luckily today, due to the courage of a few people in the room here today to make the necessary changes, women are welcome to participate fully in Ha Kol Olin and Assif.

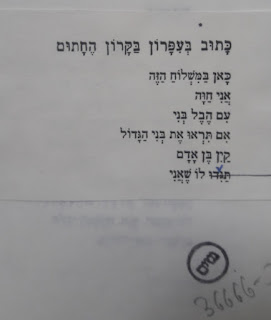

One final thought, the most fascinating part of our whole story is what doesn’t change. The immutable part that remains intact that has to be experienced rather than explained. Here we all are reading and discussing parashat Pinchas, saying the shmah, and davening Musaf, as we have for thousands of years. When we return the Torah we have to the Ark, we will sing and I will have a little catch in my throat, sometimes so much that I can’t say the words out loud…

עֵץ חַיִּים הִיא לַמַּחֲזִיקִים בָּהּ. וְתמְכֶיהָ מְאֻשָּׁר:

דְּרָכֶיהָ דַרְכֵי נעַם וְכָל נְתִיבתֶיהָ שָׁלום:

הֲשִׁיבֵנוּ ה' אֵלֶיךָ וְנָשׁוּבָה. חַדֵּשׁ יָמֵינוּ כְּקֶדֶם:

The last line comes from the end of Lamentations or Eicha where we say: ‘Take us back, O LORD, to Yourself, and let us come back; Renew our days as of old.’

Isn’t it extraordinary that we’re still grasping to that tree of life, we’re still yearning to return to the source of it all, we’re still wishing for good days like the old days. We still see ourselves as part of the Jewish journey that began so long ago and continues into an unknowable future. Shabbat shalom