It’s not surprising because Yom Kippur is a powerful day that imprints itself on us. Over and over, we resolve to be better people so that we might be be written in the book of life. We resolve to be better people so that ultimately, we will not just be written in the book, we will be sealed in the book. Gmar Chatimah tova we say. May you be well sealed. We sing a very different song today in Ha-azinu. In Ha’azinu, there is no is any Teshuva. There is no expectation that repentance by Israel will bring about a reconciliation with God.

Teshuva is a later development in Judaism and makes me once again so pleased to be a beneficiary of Rabbinic Judaism. I would rather believe that I have agency than believe that I am a victim of circumstances.

But let’s go back in time to listen to Moses’s final plea to Israel to hear his words. It is laid out as a 70-line poem. It is full of metaphors and the verses often rhyme. In it, Moses prophesies that despite all that God and Moses have said and done, Israel will abandon God, as they had in the past. God will punish Israel, as in the past, but never to the point of utter destruction. It warns that God will hide his face from Israel, and it contains these prophetic words:

‘The sword shall deal death without, As shall the terror within, To youth and maiden alike, The baby as well as the aged.’

In our long history, we have seen this happen. But I don’t believe the innocent children and old people are killed in terrifying circumstances because they are Jews who forgot God. I can’t square that circle today.

It’s interesting that Moses’s final plea to the people and his prediction is a poem because poems can express what can’t be said any other way. Poems use metaphors, and we need those to evoke something in the listener.

For example, if I say the word ‘cattle car’ in a poem and it’s read by a person who has never heard of the holocaust, they might see just see a train and they might see cows in the train, but if I say it to a Jewish person, they’ll probably see something very different. They’ll probably recall every horrendous account they’ve ever read of desperate people squashed into freight cars, without water or space to sit on the three-day journey from their village to a death camp. I don’t have to say much to evoke that. Here is a famous six-line poem written originally in Hebrew, by Dan Pagis. It is called:

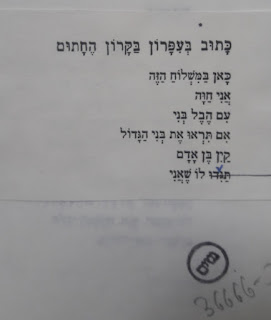

Written in pencil in the sealed freight car

Here in this carload

I am Eve

With my son Abel

If you see my older boy

Cain son of Adam

Tell him that I

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you don’t see the sealed freight car in your mind, you will miss the power of the poem. The effect is even stronger if you know that Pagis is playing with Yom Kippur liturgy, contrasting the writing (in the book of life) with the sealing in the freight car. The author of the poem knows that God hid his face from the sealed freight cars delivering millions of Jews to their death.

Eve and her son, Abel were alive then but on a journey to certain death. In our long Jewish story, we will soon take leave of the greatest prophet that ever lived. We will leave him standing on Mount Nebo and looking at the promised land from a distance. Moses is forbidden from entering it, but we are not. Soon we will continue to the next chapter in our long history of those who survived. Our story is not just written in pencil on a sealed freight cart, but also in ink on parchment and on our hearts with songs.

No comments:

Post a Comment